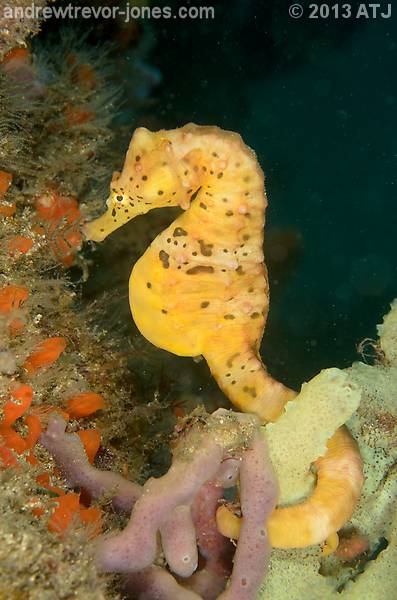

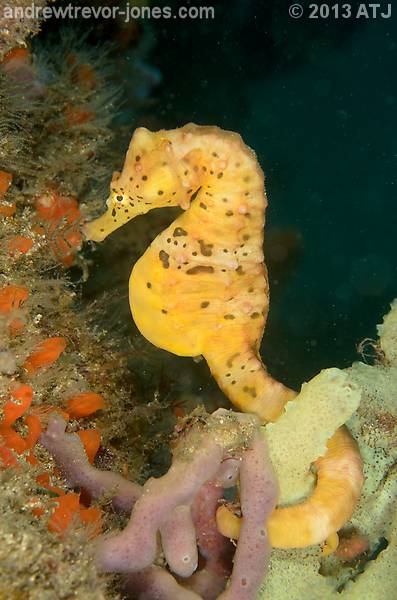

Female pot-bellied seahorse, Hippocampus abdominalis, showing the abrupt transition from abdomen to tail.

Sunday 24 January 2016

Seahorses, pipehorses, seadragons and pipefish belong to the family Syngnathidae and so are known in the scientific community as syngnathids. It sounds like a bit of a mouthful but it is generally easier to just say syngnathids rather than list the members of the family. Syngnathid is pronounced as sing-nath-id so is actually easier to say than it might look. The name means 'fused jaw' and refers to the tubular snout found in most of the species.

One of the more interesting aspects of the biology of syngnathids is that the male is responsible for the care of the eggs from fertilisation until hatching and he does this by actually carrying them around. In many species, such as the seahorses and pipehorse, he carries the eggs in a pouch. In other species, like seadragons, the eggs are carried externally on a special patch the ventral surface of the body, often the tail. The ventral side is usually the underside of the body. Note I'm saying 'ventral' not to sound clever but to include the case of upside-down pipefish, Heraldia spp., which usually swim upside-down so that their ventral side (and the side the male carries his eggs) faces up.

The fact that male syngnathids carry the eggs means that in most species there is a difference in the body form between males and females. This is called sexual dimorphism and helps us tell males from females. In some species it is quite easy and others the differences can be quite subtle making it much harder to tell them apart. Generally, seahorses and pipehorses are easy to sex. Seadragons are a little harder (unless it is a male with eggs) but the sex can usually be determined. With many pipefish species it is very difficult unless the male is carrying eggs.

I will discuss the species of syngnathids found in Sydney below but the principles generally apply to other species.

In normal seahorses (that is, not the pygmy seahorse), the difference between a male and a female is quite obvious once you know what to look for. After you get used to telling them apart it comes almost second nature and you can do it almost without thinking. The pouch on the male spans between the abdomen and the tail resulting in a more gradual transition between the abdomen and tail. When they are pregnant, the pouch is even more obvious. Females, on the other hand, don't have a pouch and so there is an abrupt transition from abdomen to tail, almost a right angle. Additionally, the abdomen on a female tends to be a bit larger as she has to be able to carry the eggs before she passes them off to the male.

Male and female pot-bellied seahorses, Hippocampus abdominalis are probably the easiest to tell apart. This is because the abdomen is more pronounced than other seahorses making the transition from abdomen to tail in females even more obvious.

Female pot-bellied seahorse, Hippocampus abdominalis, showing the abrupt transition from abdomen to tail.

Female pot-bellied seahorse, H. abdominalis.

The transition is even abrupt in a young female pot-bellied seahorses.

Young female pot-bellied seahorse, H. abdominalis.

In male pot-bellied seahorses, the abdomen is slightly less protruding and the pouch sits between the abdomen and the tail making for a much smoother transition.

Male pot-bellied seahorse, H. abdominalis, with a small pouch.

Male pot-bellied seahorse, H. abdominalis, with a small pouch.

When a male pot-bellied seahorse is pregnant, the pouch is quite obvious.

Pregnant male pot-bellied seahorse, H. abdominalis.

Very pregnant male pot-bellied seahorse, H. abdominalis.

With practice, pot-bellied seahorses can be sexed quite easily.

White's seahorses, Hippocampus whitei, don't have as large an abdomen as pot-bellied seahorses, nevertheless, it is still relatively easy to tell male from females. As with pot-bellies, the absence of the pouch in the female results in an abrupt transition between the abdomen and the tail. In most cases it is almost a right angle but sometimes it is a little more subtle.

Female White's seahorse, H. whitei.

Female White's seahorse, H. whitei.

Female White's seahorse, H. whitei.

In males, the pouch sits at the base of the abdomen creating a smooth transition to the tail.

Male White's seahorse, H. whitei.

Male White's seahorse, H. whitei.

When the male is pregnant, the difference to a female is obvious.

Male White's seahorse, H. whitei.

Note that a swollen pouch may make a right angle with the tail so the presence of the pouch should be used to indicate it is a male.

Very pregnant male White's seahorse, H. whitei.

Male Sydney pygmy pipehorses, Idiotropiscis lumnitzeri, also have a pouch for carrying the eggs from fertilisation to hatching. The way to tell males and females apart is pretty much the same as with seahorses. The only difference is the males pouch seems to take up a lot more of the abdomen with its opening being towards the front of the abdomen.

As with seahorses, the females have no pouch and so the transition from the abdomen to the tail is abrupt. Often the female's abdomen can be quite swollen but it still looks quite different to the male's pouch once you get your eye in.

Female Sydney pygmy pipehorse, I. lumnitzeri.

Female Sydney pygmy pipehorse, I. lumnitzeri.

Female Sydney pygmy pipehorse, I. lumnitzeri, with swollen abdomen.

In males, the pouch makes the abdomen a lot longer and it generally tapers to the tail.

Male Sydney pygmy pipehorse, I. lumnitzeri.

Male Sydney pygmy pipehorse, I. lumnitzeri.

Male Sydney pygmy pipehorse, I. lumnitzeri.

When they are very pregnant the opening to the pouch can be seen.

Very pregnant male Sydney pygmy pipehorse, I. lumnitzeri, with pouch opening visible.

As with the seahorses, a bit of practice can make telling the sexes apart quite easy.

Male weedy seadragons, Phyllopteryx taeniolatus, don't have a pouch like seahorses do and instead carry the fertilised eggs on a special patch on the underside of the tail. The eggs are quite obvious so if you see a weedy seadragon with eggs you can be sure it is a male. Weedy seadragons without eggs are a little more difficult to sex but females have a deeper body than males. Females carry their eggs internally until they are ready to be passed to a male and so need more room for the eggs, hence the deeper body.

In addition to a shallower body, males tend to have more of curve on the underside of the abdomen.

Male weedy seadragon, P. taeniolatus.

Male weedy seadragon, P. taeniolatus, with eggs.

Body of a male weedy seadragon, P. taeniolatus.

In some females the body is obviously deeper and there can be no question it is a female. Similarly some males have quite shallow bodies and are clearly males. The angle at which you view the seadragon makes a difference to the perception of the depth of the body. I have often seen what I thought was a male only for it to swim more vertical showing the body was deeper than first thought.

Female weedy seadragon, P. taeniolatus.

Body of a female weedy seadragon, P. taeniolatus.

Body of a female weedy seadragon, P. taeniolatus.

I will admit that I'm often not confident I know the sex of a weedy seadragon.

As mentioned above, the differences between male and female pipefish are not particularly obvious unless it's a male with eggs. I have seen pairs of upside-down pipefish, Heraldia nocturna where the male had eggs. I have also seen some pairs flag-tail pipefish in the tropics and again the male had eggs. For all other pipefish I have been clueless as to their sex.

I hope you have made it to the end of this entry and have found it useful.

Please leave Feedback if you have any comments or questions about this blog entry.